A homily by Fr. Eric M. Andersen, Sacred Heart-St. Louis in Gervais, OR

Sept 23rd, 2012 Dominica XXV Per Annum, Anno B

“Let us beset the just one, for he is obnoxious to us…let us see whether his words be true; …let us put the just one to the test.”

These words from the book of Wisdom have been repeated by countless numbers of the faithful from the time it was written before Christ and throughout the Christian era. There is something irresistible that draws us toward holy people, but there can also be something that stirs up within us suspicion and envy. How can this man or this woman be so good? Is it a deception? This was the case among the pharisees and scribes as they encountered the very Son of God, Jesus Christ, standing before them in his sacred humanity. His holiness was just too much for them to bear. He was too perfect. There was surely something deceitful going on! Of course, we know the truth about Jesus. He was God and He was the perfection of holiness; the perfection of humanity.

We also know that He came so that we could aspire to that holiness, with His help. When we are in a state of grace, we have the gifts of the Holy Spirit dwelling within us so that we can imitate Him. Each of us is called to be a saint. But aspiring to sainthood, we place ourselves under the scrutiny of others who will question our holiness. And we find ourselves questioning others saying, “Let us put the just one to the test…if he be the son of God, God will defend him.”

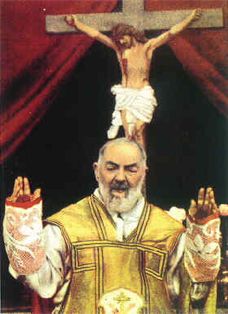

Within the living memory of many today, there is a man who drew both suspicion and devotion from the highest tiers of the Church. In the year 2006, Pope Benedict XVI made available to scholars and the faithful the Secret Vatican Archives of the Holy Office for the years 1922-1939 (cf. Castelli. Padre Pio Under Investigation, 4). Among the archives emerged a file begun in 1921 which detailed the inquisition of a Capuchin priest known as Padre Pio of Pietrelcina. Why was this priest being investigated? Because the Holy Office had received reports that he was faking the stigmata. The stigmata refers to the wounds of Christ which Padre Pio had reportedly received, piercing his skin through the hands, feet and side.

Within the living memory of many today, there is a man who drew both suspicion and devotion from the highest tiers of the Church. In the year 2006, Pope Benedict XVI made available to scholars and the faithful the Secret Vatican Archives of the Holy Office for the years 1922-1939 (cf. Castelli. Padre Pio Under Investigation, 4). Among the archives emerged a file begun in 1921 which detailed the inquisition of a Capuchin priest known as Padre Pio of Pietrelcina. Why was this priest being investigated? Because the Holy Office had received reports that he was faking the stigmata. The stigmata refers to the wounds of Christ which Padre Pio had reportedly received, piercing his skin through the hands, feet and side.

Now, let’s go back to the year 1918 when the story begins. World War I is raging. Pope Benedict XV had called this war “the suicide of Europe” urging all Christians to pray for an end to the war (cf. Wikipedia). In response, a young Capuchin priest named Padre Pio offered himself to God as a victim that the war might be ended. Within the span of about a week, Padre Pio had an experience while hearing confessions which he later described: a celestial person appeared and hurled a flaming spear into his soul. In his own words, “Since that day, I am mortally wounded. It feels as if there is a wound in the center of my being that is always open and it causes constant pain” (Preziuso, The Life of Padre Pio, 103).

A month later, in September, Padre Pio celebrated the Mass and afterwards, he was praying in thanksgiving. He later wrote about what happened next:

“I was alone. . . after celebrating Mass, when I was overtaken by a repose similar to a sweet sleep. All my external and internal senses and all the faculties of my soul were in an indescribable quiet. During this time there was absolute silence around me and within me. There then followed a great peace and abandonment to total privation of everything. . . This all happened in an instant.

While all this was happening, I saw in front of me a mysterious person, similar to the one I had seen on August 5, except that now his hands and feet and side were dripping blood. His countenance terrified me. I don’t know how to tell you how I felt at that instant. I felt that I was dying, and I would have died had the Lord not intervened and sustained my heart, which felt as if it would burst forth from my chest. The countenance of the mysterious figure disappeared and I noticed that my hands and feet and side were pierced and oozing blood” (Preziuso 106).

When it was discovered what had happened, the saint was humiliated by the attention that everyone paid to him over this. But he was at peace that he could offer this suffering up to God united to the suffering of Jesus Christ on the Cross. He had been prepared for this by Jesus who had spoken to him in prayer several years before. Jesus had said to him:

Do not be afraid; I will make you suffer, but I will also give you strength. I desire that your soul, by a daily and hidden martyrdom, should be purified and tested. Do not be surprised if I permit the devil to tempt you, the world to disgust you, persons dearest to you to afflict you, because nothing can prevail against those who mourn beneath the cross for love of me and whom I exert myself to protect [(Epistolario, I, 339) Preziuso 139].

Shortly after this happened, word got out and people began flocking to see Padre Pio. Word even reached the Vatican. In response, Fr. Agostino Gemelli, OFM, visited the convent of San Giovanni Rotondo where Padre Pio lived. Gemelli was a disinguished scholar who doubted the authenticity of the stigmata (cf. Castelli 5). He immediately wrote a personal letter to the Holy Office in Rome declaring it “the fruit of suggestion” (5). Thus began the formal inquisition.

Shortly after this happened, word got out and people began flocking to see Padre Pio. Word even reached the Vatican. In response, Fr. Agostino Gemelli, OFM, visited the convent of San Giovanni Rotondo where Padre Pio lived. Gemelli was a disinguished scholar who doubted the authenticity of the stigmata (cf. Castelli 5). He immediately wrote a personal letter to the Holy Office in Rome declaring it “the fruit of suggestion” (5). Thus began the formal inquisition.

In June of 1931, a letter arrived from Rome restricting the priestly faculties of Padre Pio. He was no longer allowed to celebrate Mass publicly nor to preach nor hear confessions. News quickly spread and the people protested outside the convent. Padre Pio accepted this decision and offered it up. After all, it was God’s work, not his. God could accomplish far more, if He chose, by his humiliations and suffering than by his priestly ministry. Pope Pius XI came to his rescue and released him from these restrictions in 1934. From that time crowds began to flock to San Giovanni Rotondo to go to Confession to Padre Pio. He would sit in the confessional for hours upon end. He could read people’s souls, even recognizing sins that they withheld from him. But he did not judge them. He wished them to be set free. He loved them and so he became known for not giving absolution if they were there for the wrong reasons. Those who came to him insincerely, to test him, to mock him, or just to visit a celebrity priest, were sent away.

But he warned other priests not to copy him in this practice. He said: “You cannot do what I do!” (Preziuso 151). “All those who experienced the bitterness of being sent away without absolution, eventually, through the prayers of Padre Pio, were moved to true remorse. They were not at peace! They lived in a state of constant, unbearable agitation which ended only when, after a radical change of life and a total conversion, they turned to the heavenly Father with sincere repentance. Then their laments of sorrow turned into shouts of joy” (151). And Jesus would sweetly say, “Ego te absolvo” through the ministry of His priest. Meanwhile many people were experiencing miracles of healing and conversion. But the investigation of Padre Pio continued throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s. It was even discovered that one of the friars had placed a bug in various places to record the private conversations of Padre Pio.

In 1962, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla wrote a letter to Padre Pio asking him to intercede and pray for a 40 year old woman in Krakow who was suffering greatly from cancer. Wojtyla had met the priest many years before while a seminarian in Rome. Padre Pio read the letter and said: “To this I cannot say no” (206). Ten days later, another letter arrived from the future Pope John Paul II. The letter read that as the woman was about to undergo surgery, her cancer “was suddenly cured” (206). Cardinal Wojtyla thanked Padre Pio for the favor.

September 20th, 1968 marked the fiftieth year of his receiving the stigmata. These wounds had soaked innumerable bandages with his blood for 50 years. The wounds of Christ which he carried had been examined time and again by skeptical doctors and scientists, humiliating him and scoffing at him. Two days later on September 22nd, he celebrated a sung Mass at 5 o’clock in the morning. The church was packed with 740 prayer groups. At the consecration, someone noticed that his hands were smooth and clear. There was no visible stigmata. After the Ite Missa Est was intoned, Padre Pio collapsed. That night, he made his last confession in anticipation of his death. He died very early in the morning on September 23rd, 1968, repeating the words, “Jesus, Mary, Jesus, Mary.”

When they examined his dead body, there were no marks, no scars, no trace that there had ever been a stigmata. His skin was smooth and elastic. Those who examined his body concluded that, among other things, this healing was a sign of the Resurrection, when the body will be restored to its perfection after death. He had suffered for Jesus Christ in life. His wounds were no longer needed after death. His body remains incorrupt to this day. Padre Pio was canonized a saint by Pope John Paul II in 2002. Padre Pio did not seek greatness. He sought to be the last and the servant of all. In this, God exalted him and defended him and took him to Himself.

When they examined his dead body, there were no marks, no scars, no trace that there had ever been a stigmata. His skin was smooth and elastic. Those who examined his body concluded that, among other things, this healing was a sign of the Resurrection, when the body will be restored to its perfection after death. He had suffered for Jesus Christ in life. His wounds were no longer needed after death. His body remains incorrupt to this day. Padre Pio was canonized a saint by Pope John Paul II in 2002. Padre Pio did not seek greatness. He sought to be the last and the servant of all. In this, God exalted him and defended him and took him to Himself. For more homilies by Fr. Andersen, click on the tab at the top of the page.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please be courteous and concise.